Highlights

- Long-term Treasury yields have climbed since Trump’s election, partially from concerns that tariffs would stoke inflation.

- Tariffs would certainly mean higher prices in the US. But they would not kindle inflationary risks.

- With the post-election surge in yields providing a nice entry point, we’ve shifted to a positive view on duration.

If there’s one thing tariffs are good at, it’s getting economists talking. Can tariffs prevent offshoring? Can they foster critical industries and bolster national security? Do they create jobs? Destroy jobs? Both? The debates will never end.

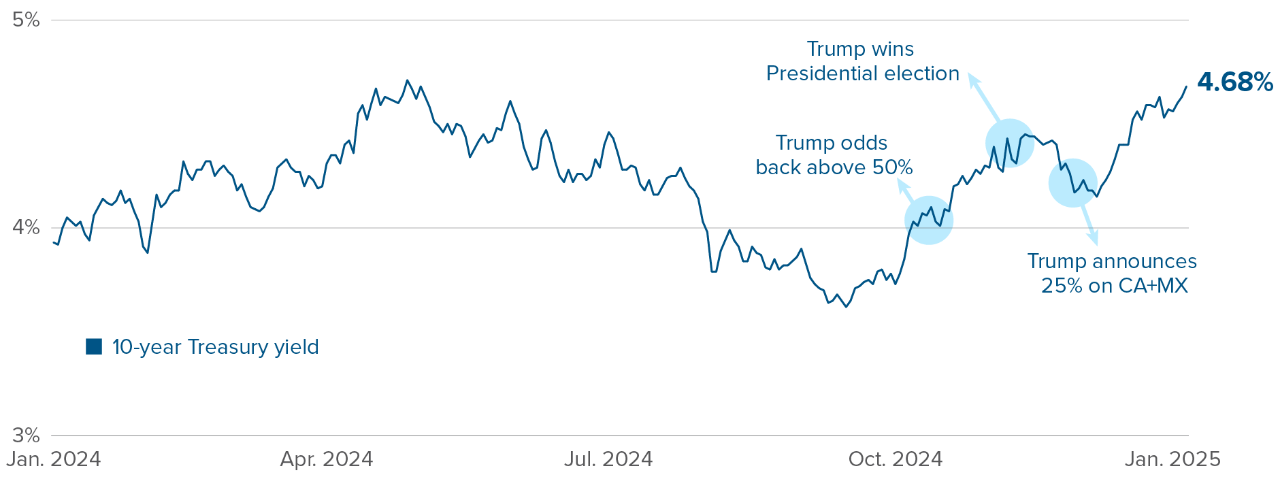

Markets have particularly keyed in on one ostensible byproduct of Trump’s tariffs: inflation. In some investors’ view, Trump’s universal tariffs could reignite the inflationary tide that terrified bond markets back in 2022-2023. This anticipation of tariff-driven US inflation contributed to the almost 0.8% rise in 10-year Treasury yields seen since Trump’s election odds began taking off in early October.

Figure 1: Tariffs strike fear in bond investors’ hearts

10-year Treasury yield vs. Trump headlines

Source: Bloomberg. Trump odds of winning the 2024 Presidential election taken from the PredictIt and Polymarket betting markets.

Source: Bloomberg. Trump odds of winning the 2024 Presidential election taken from the PredictIt and Polymarket betting markets.

Tariffs on imports are not inflationary, in most cases. Inflation, from a central bank’s point of view, is a sustained rise in prices. If the central bank does not step in to nip inflationary shocks in the bud, the price level will keep drifting higher, with an inflation rate de-anchored from its target. In contrast, tariffs will cause a one-time jump in prices, as import prices for targeted goods increase. But once the tariff shock has passed, prices return to their 2% target growth trend.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) can safely look through tariff-driven price increases. Because tariffs cause a one-time shock to the price level, and central bank rate hikes take time to act, raising rates to prevent consumer prices from adjusting to tariffs is a fool’s errand. Plus, since prices will return to their 2% trend path once the tariff shock has passed, reacting to tariffs with hikes could cause inflation to undershoot its target in the future. In its September 2018 Tealbook forecasting publication, the Fed ran a scenario analysis for 15% tariffs on all non-oil imported goods. It concluded that the appropriate response would be to look through the resulting price increase.

Figure 2: Tariffs cause higher prices, not faster inflation

Consumer price index under various shocks, 0=100

Source: Author’s scenario. Illustration purposes only.

Source: Author’s scenario. Illustration purposes only.

In fact, over a few years’ horizon, tariffs could lower inflation. In figure 2, the orange line could have a slope below 2% in the out years. Acting as a tax on consumers and an irritant for domestic factory production, especially if intermediate critical goods are targeted, tariffs could cause consumers to skimp on consumption and compel businesses to fire workers. Morgan Stanley economists estimate a 1.4 percentage point hit to US GDP growth from US tariffs.

There is one specific scenario in which tariffs trigger sustained inflation. If the initial price shock is large enough, consumers and businesses might believe that the shock is long-lasting, making them doubt the Fed’s willingness and ability to stabilize prices. But the most likely scenario in our view — 10% universal tariffs on non-oil goods, plus 40% tariffs on Chinese goods — would cause consumer prices to jump by an estimated 1.5%, insufficient to cause fears of an inflation spiral.

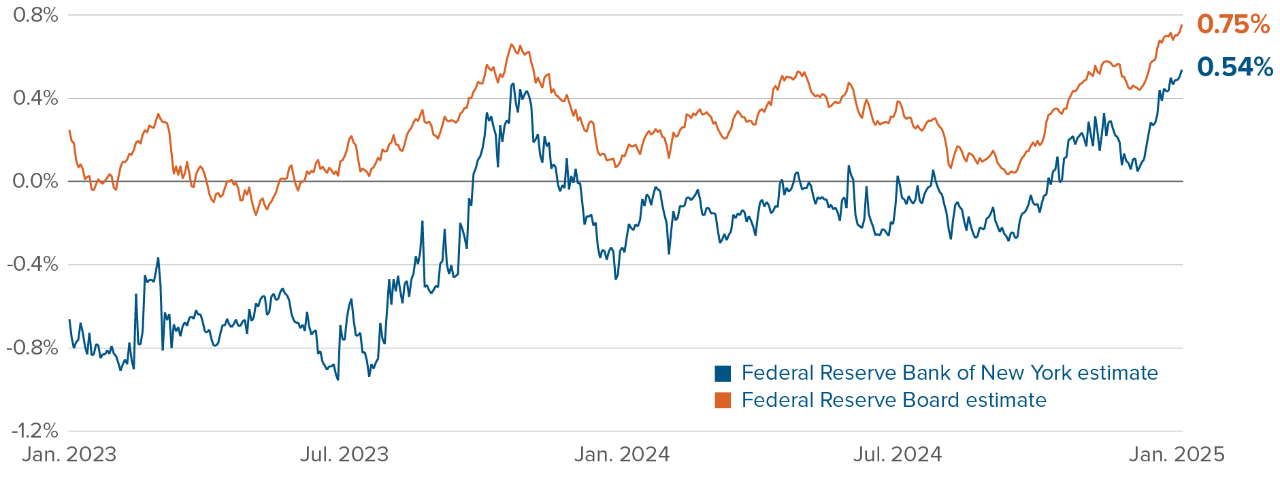

In short, a bond sell-off driven by fear of a trade war is a good buying opportunity, in our view. It’s unclear whether the new tariffs would prod the Fed to keep rates higher than in a world without them. Estimates of 10-year Treasury term premium — a measure of the extra compensation an investor can expect to receive by buying longer-duration bonds — have risen sharply in recent weeks.

Figure 3: Get paid to go long

Term premium, 10-year Treasury notes

Source: Bloomberg. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimate uses the Adrian, Crump and Moench (2013) model. The Federal Reserve Board estimate uses the Kim and Wright (2011) model.

Source: Bloomberg. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimate uses the Adrian, Crump and Moench (2013) model. The Federal Reserve Board estimate uses the Kim and Wright (2011) model.

In addition to tariff fears, Trump’s election also brought prospects of higher federal government deficits. Now, that presents an unambiguous inflation risk. Permanent deficits cause the kind of sustained inflation illustrated by the grey line in the second chart above. To avoid the inflation rate from merging into the express lane, the Fed would have to raise rates and keep them high.

But, as explained in last month’s commentary, the nomination of Scott Bessent as Treasury Secretary and Elon Musk’s small government proselytizing suggest that the deficit might not blow up after all. Plus, over recent weeks, Trump advisors repeatedly voiced their plan to scrap a chunk of the subsidies from Biden’s Inflation Reduction Plan. We expect deficits to stay in the 7%-8% range for the coming two years — in the ballpark of the Biden administration’s deficits over the past few years — before dipping towards 5% in 2027-2028. These high single-digit deficits will stimulate the US economy, likely preventing the Fed from bringing rates back down below 3%. But they don’t represent a hard break with the Biden fiscal paradigm.

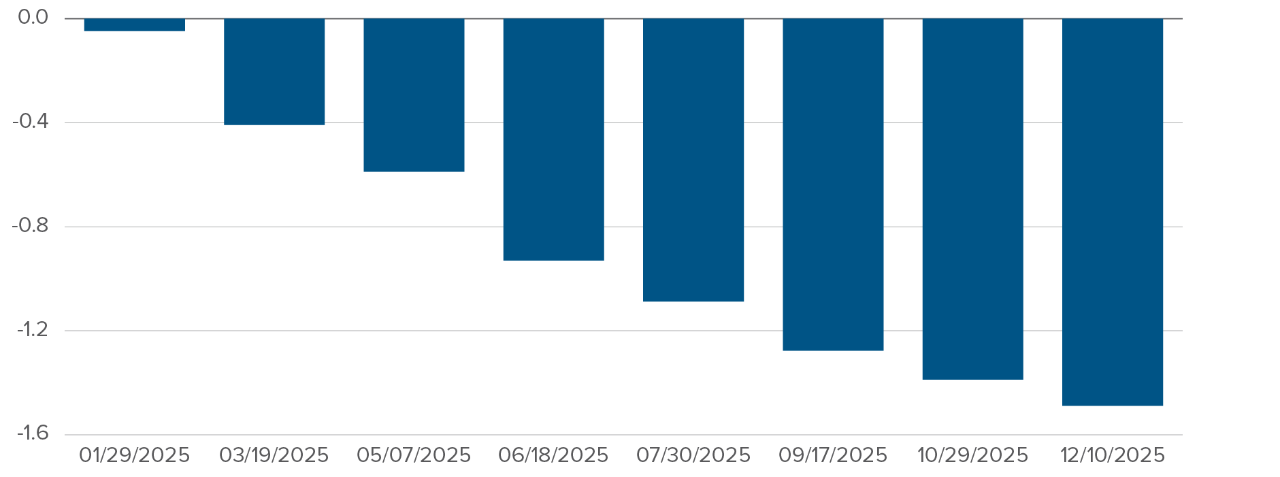

Markets expect the Fed to only cut rates once or twice in 2025, partly because of tariff risks. In our view, the Federal Reserve will have to cut at least three times, to prevent the job market from sliding further. Inflation is sticking around 3%, but the current Fed has shown a willingness to look away from consumer prices when growth tanks.

Figure 4: The US economy won’t stabilize with only one rate cut in 2025

Market expectations, Federal Reserve rate cuts

Source: Bloomberg. Market rate cut expectations are derived from overnight interest rate swaps.

Source: Bloomberg. Market rate cut expectations are derived from overnight interest rate swaps.

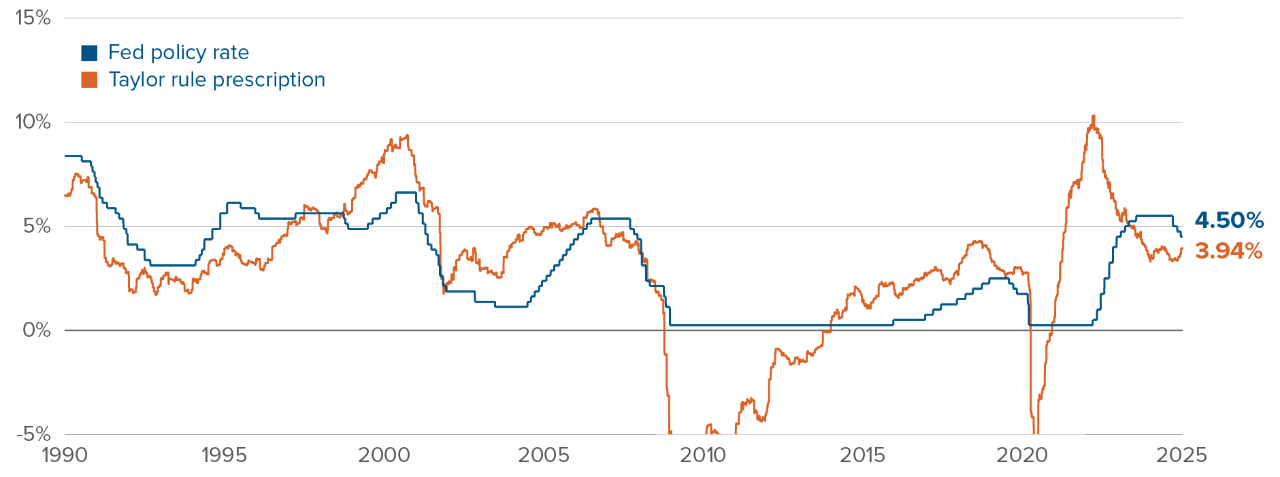

Even considering the tariff and deficit uncertainty from Trump’s election, rates are higher than they should be. Our real-time Taylor rule, which bakes in the average economic forecasters’ 12-month-ahead views on growth and inflation, is prescribing a policy lending rate around 3.9%.

Figure 5: There’s no emergency to cut, but rates can’t stay at 4.5% through 2025

Real-time Taylor rule prescription

Source: Calculations by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Source: Calculations by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

For investors, the ultimate value in holding long-term government bonds is protecting portfolios from recessions. We are not forecasting a recession in the US, even with a trade war potentially shaving off upwards of one percentage point of GDP. The US economy remains resilient, even if it has moderated since the second quarter of 2024. Plus, the Fed has shown it was ready to react quickly to a deterioration in growth. It should be reactive enough to fend off recessionary scares.

However, the 3% US GDP growth rate of the past few years is unlikely to repeat. Long-term Treasuries are now attractively priced for a scenario of middling growth and high-but-stable inflation. Accordingly, we are slightly long Treasuries in the Mackenzie Global Macro Fund.

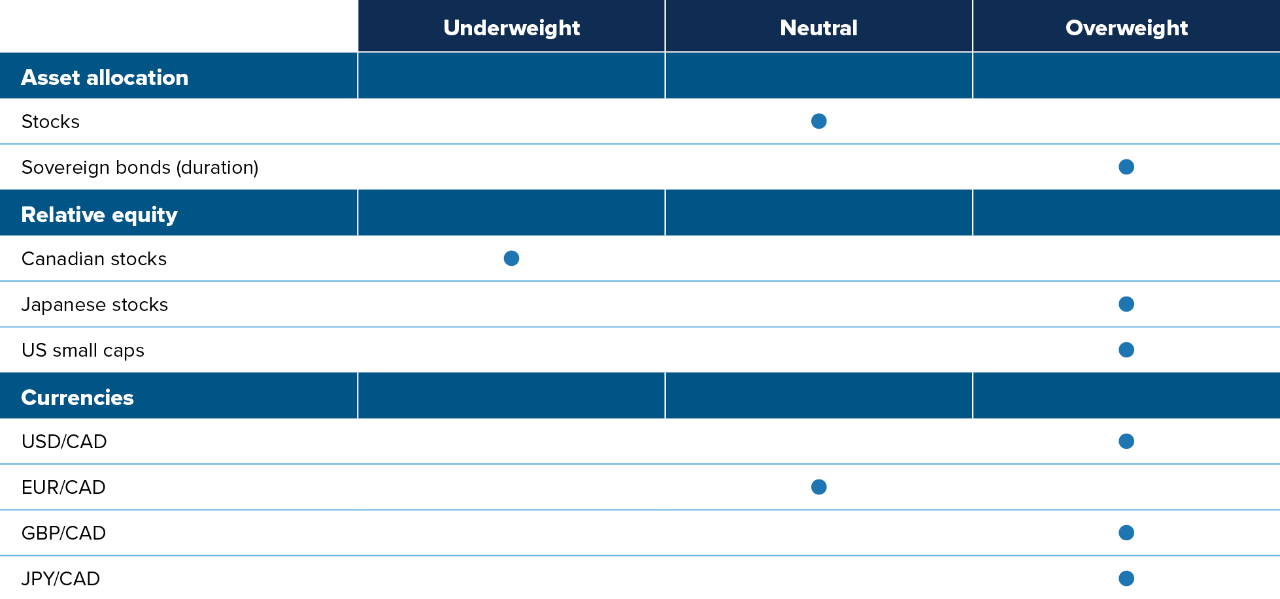

Multi-Asset Strategies Team’s investment views

Tactical summary

Source: Mackenzie Investments

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Source: Mackenzie Investments

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Turning positive on duration: We’ve mostly shied away from duration over the past few years. We preferred leaning into stocks for returns and saw US recession odds as overblown. We still don’t expect a recession anytime soon, given the US government’s continuing deficits and the Federal Reserve’s eagerness to cut rates ahead of a contraction. But we also don’t see high risks of an inflation surge over the next few quarters, the ultimate risk for fixed income. Trade tariffs would cause prices to jump in the US but are not an inflationary shock. Once the one-time effect on prices has passed, future inflation could be lower than without the tariffs, given trade wars could depress economic growth. With government bonds selling off in recent weeks, yields are now attractive enough to tempt us to buy long-term bonds in such an environment.

Still not ready to bet against equities: While global stock markets are clearly expensive, valuations are not at extremes, like they were, for example, at the end of 2021. Investor positioning is supportive in the medium term, and we expect the US to avoid a recession as a slew of rate cuts help stabilize the economy. This leaves us with a broadly neutral view on global equities.

Still bearish on the euro: In November, we closed our euro overweight. Financial market inflows have been turning into outflows in recent months, a bad omen for the euro. Plus, revised estimates of long-term euro fair value, using recently released macro data, suggests that the euro is less cheap than previously thought. Even with the euro underperforming most developed market currencies in the fourth quarter of 2024, it remains too expensive given the economic weakness and political risks in France and Germany.

Upside potential in small caps: Small cap stocks are not a bargain, but they are somewhat cheaper than large cap stocks across sectors, as November’s commentary outlined. Small caps’ window of outperformance is narrow: it requires both Fed rate cuts and a resilient US economy. But if the post-Covid economic overheating does resolve with a soft landing, the valuation gap between small and large cap could close quickly.

Canadian landing: The macro situation in Canada is much more dire than in the US. The Canadian economy has an argument for the most disappointing advanced economy in 2024. The job market is deteriorating quickly, especially when adjusting for working population growth and government hiring. We like Canadian government bonds, but dislike Canadian stocks and the Canadian dollar. Looming US tariffs on Canadian exports are an additional risk, with President Trump recently singling out Canada as a tariff target. We’ve taken some gains in our short position in the Canadian dollar, but still expect it to underperform most other currencies globally. $1.45 USDCAD is still within reach.

Commodity-exporting EM currencies: Commodity-exporting EMs are well situated to outperform in this macro environment. Their budgetary and external balances have improved amid high global nominal growth and high commodity prices. Their central banks started raising rates much earlier than the rest of the world. On the other hand, we hold a negative view on the currencies of Asian EM countries. Their external positions have severely deteriorated, and their interest rates are relatively low. Thailand’s prospects have improved significantly, but South Korea and the Philippines are still stuck in the macro mud. An attempted self-coup in South Korea in December added uncertainty to prospects for the Korean economy.

Doubling down on European duration: Inflation rates have been pulling back in a synchronized manner across euro area countries. In recent weeks, even solid-but-unimpressive economic indicator prints have been met with rallies in long-term rates, as markets price out the right tail scenario of an inflation spiral. At the other end of the spectrum, United Kingdom and Australian duration are less attractive.